The risky business of social business – and how to manage it

Directors and trustees of social ventures can focus too heavily on the financial aspects when it comes to risk management – which might actually undermine their efforts to achieve positive social impact, warns Tom Beswick of Buzzacott accountants.

Risk management and determining appetite for risk is a crucial part of effective governance in any entity.

Typically, this begins with a broad consideration of a range of risks, for each of which the process will be:

- Identify the risk, ideally with reference to strategic or organisational objectives;

- Decide on what the most appropriate response is to mitigate that risk; and

- Monitor the risk to decide whether a different course of action is needed.

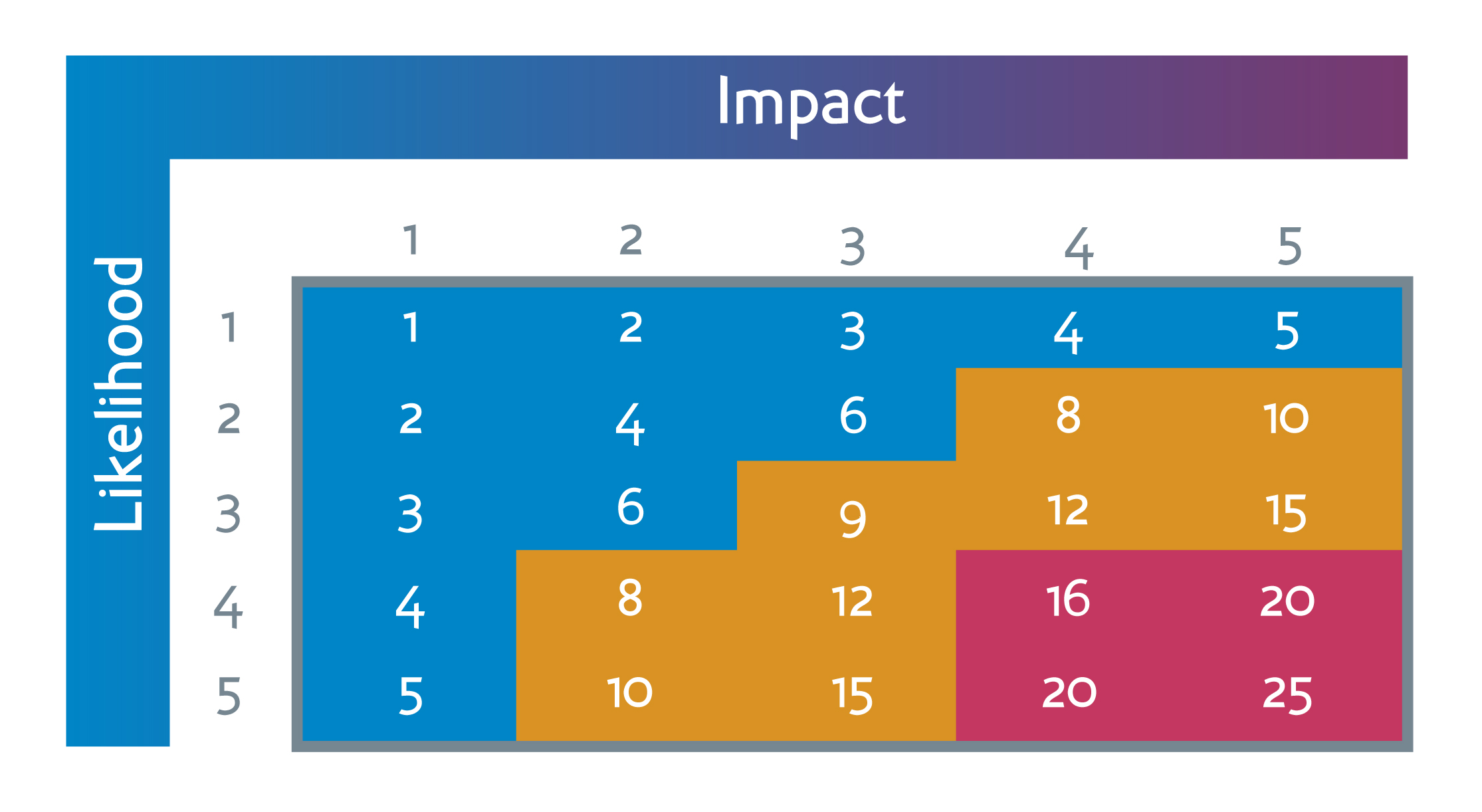

Risks will be ranked depending on a combination of their likelihood of arising and how significant their impact would be to an organisation if they were to arise. This is usually recorded in a register which may include visual representations that highlight the ranking of likelihood and impact of each identified risk, such as the example below.

However, there is a tendency for a board of directors or trustees to focus too heavily on interpreting impact as financial impact or disruption impact, rather than social impact. This can hinder forming a nuanced view of risk and prevent organisations from maximising their social impact. For social purpose organisations this frustrates achieving what should be the primary goal.

The risk of some financial pain on a more minor scale may be worth taking in order to help further the organisation’s social impact.

Whilst an entity aiming to maximise its social impact is entirely right to avoid taking risks that would have a significant financial and operational impact on the organisation, the risk of some financial pain on a more minor scale may be worth taking in order to help further or even develop an alternative method to furthering the organisation’s social impact.

Altering the impact lens

One example that can be used to demonstrate this is the differing attitudes towards risk that a commercial financial institution (let’s call it Company A) may take as opposed to a social financial institution (Company B).

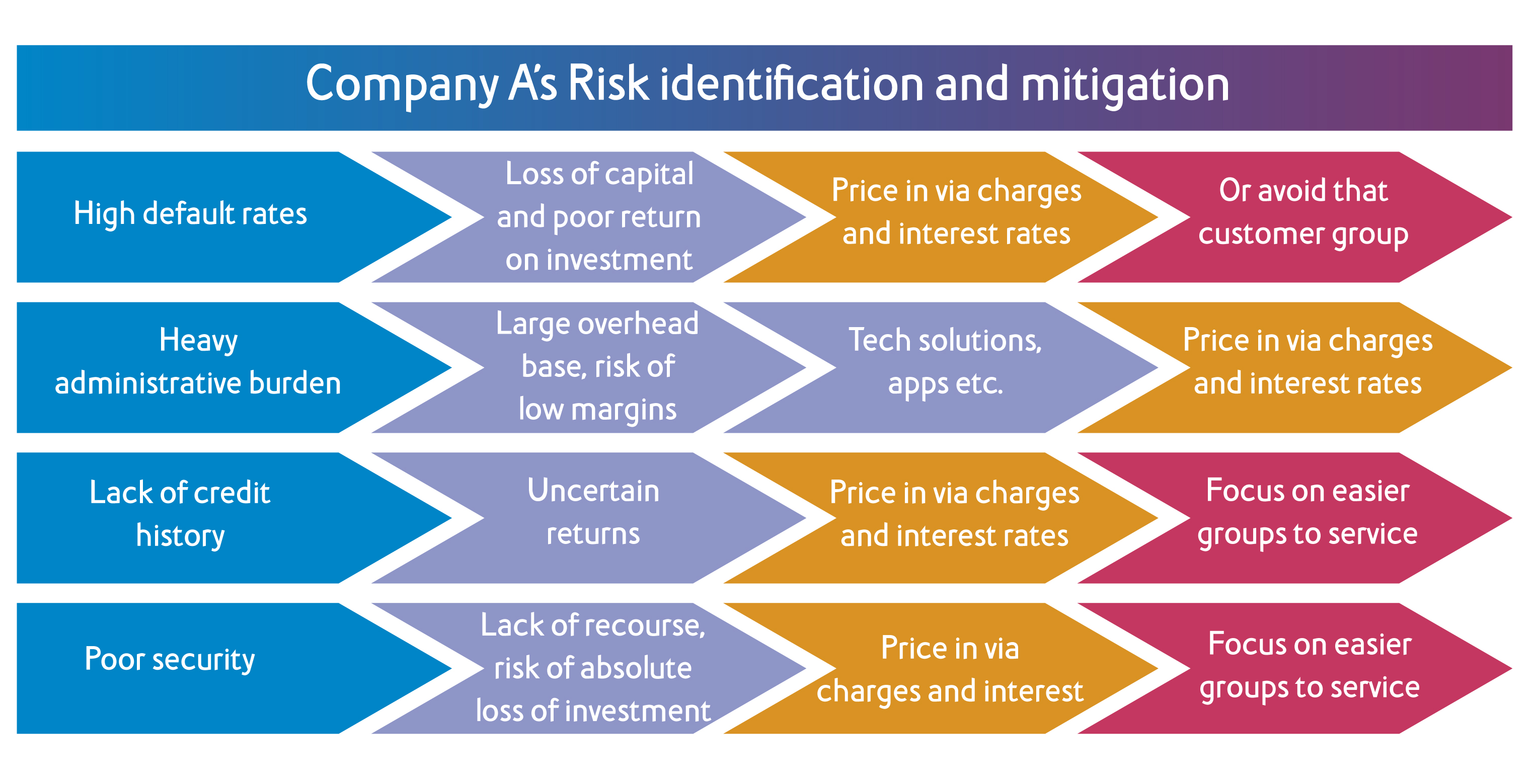

On one hand, Company A’s primary concern is to obtain a satisfactory monetary return from providing finance in exchange for interest and charges and after providing for expected defaults. It may conclude that the key risks that could impair this return include:

High default rates; a heavy administrative burden; a lack of decision making data (such as credit history); and poor security.

Measures that it could take to mitigate these risks include pricing in higher interest rates and charges for those it considers at greater risk of defaulting or, if considered too great or unquantifiable a risk, avoiding that group altogether.

Although this risk assessment is rational given the criteria applied, it has the social consequence of excluding entire groups of people from obtaining finance

Company A might even conclude that it is right to focus its efforts on those customer groups that it is easiest to service. Although this risk assessment is rational given the criteria applied, it has the social consequence of excluding entire groups of people from obtaining finance, or if they do only at a rates of interest and charges that make finance unaffordable and / or lead to problem debt.

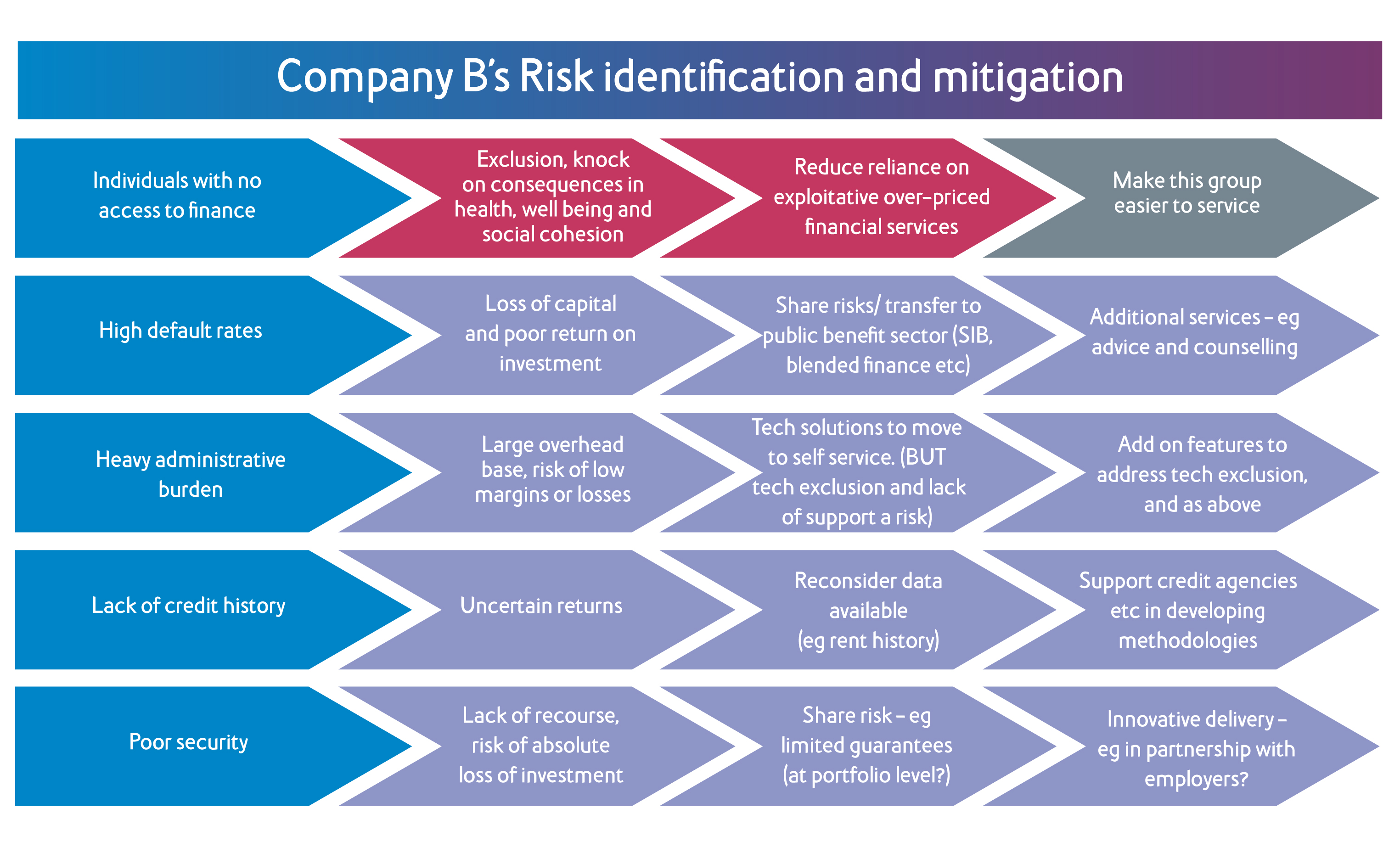

On the other hand, Company B is an organisation that aims to make affordable finance more easily accessible for those who have historically been poorly served by the market. Whilst it also needs to ensure that it does not take risks that would jeopardise its financial and operational standing, addressing financial exclusion as the primary, non-negotiable objective fundamentally changes how it responds to the same risks that have been identified by Company A.

Company B addressing financial exclusion as the primary, non-negotiable objective fundamentally changes how it responds to the same risks that have been identified by Company A

For example, where Company A tried to compensate lending to those with a lack of credit history with higher interest rates, Company B may decide to look at alternative data such as rent history to enable lending to those with track records of meeting commitments without imposing the additional burden of higher borrowing costs. This could in turn enable credit agencies to develop new methodologies for assessing credit ratings.

Considering the risk of default and managing relationships in groups where alternative data is not available, a socially motivated business might seek other ways to cover the greater costs. For example, it may seek to source grant funding (perhaps from government or a charity with compatible objectives) to support the higher overhead costs of lending to financially excluded groups.

We can see how applying the impact lens for Company B results in a reduced tendency to avoid the activity. It drives an increased commitment to finding new ways to replace unmeasured uncertainty with measured and manageable risk. It also leads to a greater commitment to seeking ways, where appropriate, to transfer or share the risks with other parties who may have the same mission.

The above example sets out some concrete differences in behaviour that can result from an increased focus on mission related criteria in risk assessment. The principle is no less relevant to other social or environmental objectives; for example, access to employment, minimising environmental impact or addressing historic social injustices.

Don’t be counterproductive

Organisations that have both business and public benefit objectives should consider circumstances and events that might impact each of these when undertaking a risk assessment.

Addressing only financial and operational risk can lead to counterproductive actions which frustrate fundamental objectives. Properly addressing social and environmental impact risks can lead to innovation that both delivers against our core purpose and provides examples that ‘mainstream’ business would do well to adopt.