Hong Kong: Unis must do less theory and more practice to create social change

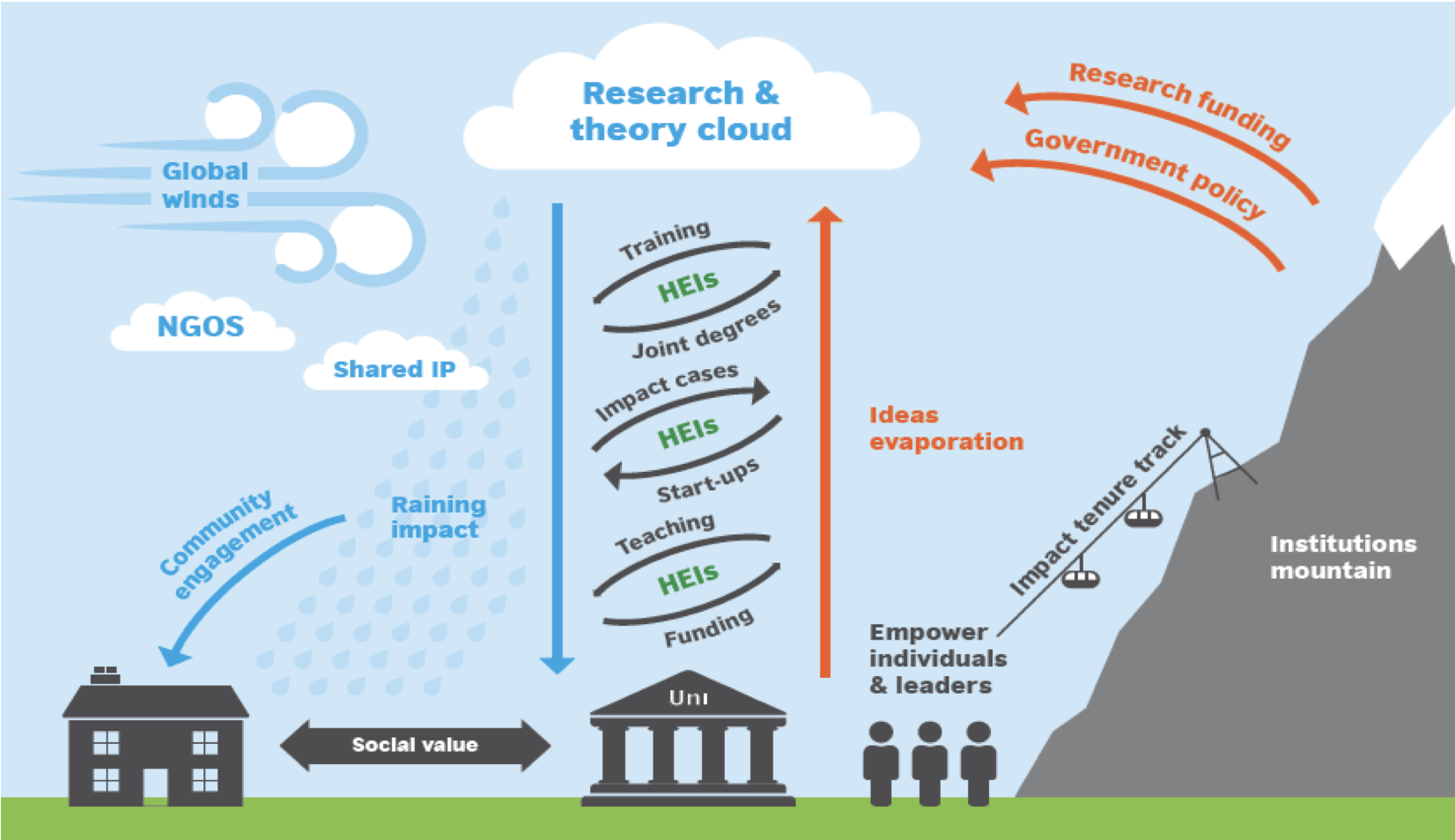

There is no shortage of social innovation programmes in Hong Kong’s universities, but new research shows that scholars need to engage in more practical activity and collaborations outside academia to really tackle the territory’s social challenges.

Social impact has been a buzz-phrase in universities across the world for many years. But how easy is it to work collaboratively with public and third sector organisations when academics are on the “publish or perish” treadmill?

A new report, Surveying the Landscape of Social Innovation and Higher Education in Hong Kong, which was commissioned by the British Council in Hong Kong and published in September 2019, says universities should do less theory and more practice to have a genuine social impact. It argues that social innovation – which broadly means finding innovative solutions to social and environmental problems – faces structural barriers in connecting teaching and research to much-needed social change in the community.

Dr Yanto Chandra, co-author of the report and associate professor at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, says: “While the main finding of the report shows that social innovation research and teaching is growing in Hong Kong, the research shows that there is a lack of collaboration amongst higher education institutions and between higher education institutions and the wider community. Collaboration is often not an easy thing to do across institutions and sectors but it is necessary since no single person or organisation owns all resources and knowledge to solve problems.”

The best and most impactful social innovations usually, through successful collaboration, bring about some sort of systemic change

Jeff Streeter, the director of the British Council in Hong Kong, echoed this point writing in the Times Higher Education online recently. He said: “Unlike the more traditional top-down and many technology-driven innovations, social innovations are more likely to be bottom-up and powered by the community, working in collaboration with people and institutions from a number of different sectors, including higher education, business, government and NGOs.”

He added: “The best and most impactful social innovations usually, through successful collaboration, bring about some sort of systemic change.”

The team of British and Hong Kong academics interviewed scholars working within social innovation in Hong Kong alongside conducting a systemic mapping of research, teaching and knowledge exchange in the Hong Kong social innovation ecosystem. The research also found that there is a lack of applied research in social innovation and there are barriers to academic engagement because of career structures.

“There is a very high level of rigour in terms of what universities want from academics – research papers in esteemed journals and research grants. And the type of funding that goes into supporting this is very scholarly – we produce great research and teaching, but there is room for more practical applications,” says Chandra.

But is the landscape for social innovation changing?

Chandra says that, unlike social innovation in the UK and US which came from the grassroots, in Hong Kong, social innovation was originally a government initiative. “The early seeds of this lies in the government trying to reduce welfare and get people to work right after the Asian financial crisis and austerity programmes.” Among other funding initiatives, the government set up the Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship Development Fund (SIE Fund) with HK$500m.

While progress in higher education institutions has been slow, all eight Hong Kong universities have joined the BRICKS consortium (Building Research Innovation for Community Knowledge and Sustainability), a British Council initiative to encourage collaboration between universities, NGOs, social enterprises and other organisations. Backed by HK$3.5m of SIE Fund money, BRICKS has recently launched eight collaborative social innovation projects, from dementia planning to natural and community heritage tourism (see box below). Chandra argues that BRICKS could bring social innovation activity in Hong Kong to “a new level”, allowing academics to work together to “co-craft” large grants. In an exciting development, his own university is setting up a Centre for Social Policy and Social Entrepreneurship.

Collaboration in action: Nurturing Social Minds

One example of a successful collaboration in Hong Kong is Nurturing Social Minds (NSM), a social innovation teaching programme based out of three Hong Kong universities: The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) and Hong Kong Baptist University. At CUHK, the NSM course is called “Social Enterprise and Impact Investment” and is delivered to mostly MBA students, who work with a social venture organisation to “address challenges, capture potential opportunities and obtain support from the ecosystem to ensure sustainability of the business”. Student teams showcase their work, and the winner receives a HK$250,000 grant.

The idea for NSM came from Yvette Yeh Fung, chair of Yeh Family Philanthropy. It is funded by the SIE Fund, which provided scale-up costs, and Yeh Family Philanthropy, which pays for the grant award to the winning collaboration.

The course delivers real social impacts, says Elsie Tsui, adjunct associate professor at CUHK and course instructor for the NSM programme there: “One example is that a social venture partner – a health tech startup – adopted the suggested sales and market channel proposed by the students. This helped the startup to speed up its market launch, and they were able to create more impact at a faster pace.”

Tsui says that the course exists as a practicum – a practical course of study – which is popular among MBA students. It allows the tutors to innovate within the existing system. Chandra also suggested that collaboration may be easier at master’s level, where there is “freedom for the course leader to design a course and involve other parties”.

“If we are going to learn from this case, it could be that we need to start at master’s level,” he says.

Chandra says he would like to see more higher education champions of social innovation, more centres of excellence, more networking and conferences and a greater number of social innovation professors – even ones sponsored by global companies. For now, he and others are working hard at building informal collaborative relationships. In many ways, he is making small-scale, informal networks needed for social innovation research and practice in Hong Kong.

“I’m very optimistic about the field. We just have to acknowledge the reality before we can open new doors,” he says. “And that’s what the report aims to achieve.”

New collaborationsThe BRICKS project has recently announced eight new social innovation initiatives that are collaborations between Hong Kong higher education institutions and third sector organisations. They are supported by the SIE Fund and include: • Solution Scalability: Bringing together The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, The University of Hong Kong and the Jockey Club Design Institute for Social Innovation, researchers will analyse startup proposals to discover what makes a solution scalable and sustainable. • Precarious Workers’ Platform Co-op: The Chinese University of Hong Kong’s centre for social innovation studies will work with the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions to interview workers in unstable employment to explore how a digital platform to provide a service or product which is collectively owned by the workers could help reduce their difficulties. • The Tai O Village Community-led Social Innovation for Social Inclusion Study: Tai O Village is moving from a fishing and agriculture-led economy to one based on tourism. Researchers from The Hong Kong Polytechnic University and The Chinese University of Hong Kong will work with Tai O YWCA and local residents to ensure that tourism development strategies also increase social inclusion. |