Meet Pakistan’s barefoot entrepreneurs

The elite will never help the poor, believes Pakistan’s famous architect Yasmeen Lari, so she has spearheaded a project to train beggars to become skilled craftspeople enabling them to earn their own living. Our DICE Young Storymaker, Adeel Ahmed, reports from Makli in southern Pakistan.

There was a time when Marbee (pictured top, next to one of her sons) used to spend the better part of her days begging on roads and near crowded bazaars under the scorching sun in one of southern Pakistan’s poorest regions.

It was a life of uncertainty and hardship, one which she had to endure only to return home at the end of the day with a paltry 100 Pakistani rupees (50p) or less, collected through begging. For food, her family often depended on the small portions given out at local soup kitchens.

In late 2018, however, when an opportunity for a better life knocked at Marbee’s door, she decided to embrace it – by enrolling in classes to learn the craft of ‘Kashi’ (glazed tile work and terracotta art).

Marbee is one of more than 200 people from eight villages, all belonging to former mendicant (people who live on alms) communities, in Makli region of Sindh province who have been trained as part of the ‘Green Skills and Crafts for Livelihoods’ project — a collaboration between the Heritage Foundation of Pakistan and University of Glasgow, supported by the British Council.

The impoverished communities live in the shadow of the vast Makli Necropolis, a cemetery containing half a million tombs and graves and a Unesco World Heritage Site. The villages lack the grandeur enjoyed by the much-frequented tourist destination. According to World Bank estimates, about 34.2 per cent of the population in Sindh lives in poverty and rural-urban disparity in the region is very high. The numbers are bleaker in the province’s Thatta district — which is home to Makli — where close to half the residents live in poverty.

For Marbee, however, a year’s worth of training has meant that she no longer needs to ask for charity on the streets to feed her six children. The products she and other villagers make are sold in other villages and at exhibitions, with the craftspeople being paid on a biweekly or monthly basis.

Marbee and other villagers use moulds to make clay products. Photo: Adeel Ahmed

“I find it easier to make ends meet now … life is better,” Marbee, who now earns 400 rupees (£2) a day, tells Pioneers Post. She says her family is now also able to save money to occasionally purchase things like jewellery for her young daughter and a goat for the household.

Mother Earth products

The participants from the eight Makli villages have been given hands-on training at workshops to produce a range of – as the Heritage Foundation calls them – ‘Mother Earth products’, articles using mostly organic materials with a zero-carbon footprint.

Each village specialises in a certain type of product, which include glazed tiles, ceramic goods, bamboo furniture, Moringa powder, mud bricks, organic soap, homemade yoghurt, ‘Pakistan 'chulah' (earthen smokeless stoves) and compost. In addition, the villagers are taught techniques to grow vegetables at the local nursery.

The villagers are trained at the Zero Carbon Cultural Centre in Makli, which has been transformed into a colourful social space where the local women and youth can come and go, besides joining in the workshops.

The Zero Carbon cultural Centre in Makli where villagers are trained. Photo: Heritage Foundation of Pakistan

The project aims to develop expert artisans, or “barefoot entrepreneurs” as the Heritage Foundation calls them, who it is hoped will teach the craft to their fellow villagers — thus enabling the communities to start earning through their interconnectedness, without having to depend on city folk.

This unique model of interdependence is the brainchild of Yasmeen Lari, the CEO of Heritage Foundation and Pakistan’s first female architect (she opened her practice, Lari Associates, in 1964 after studying in the UK). She says she wants to see the villagers buy from each other because, she argues, the elite “will never help the poor”.

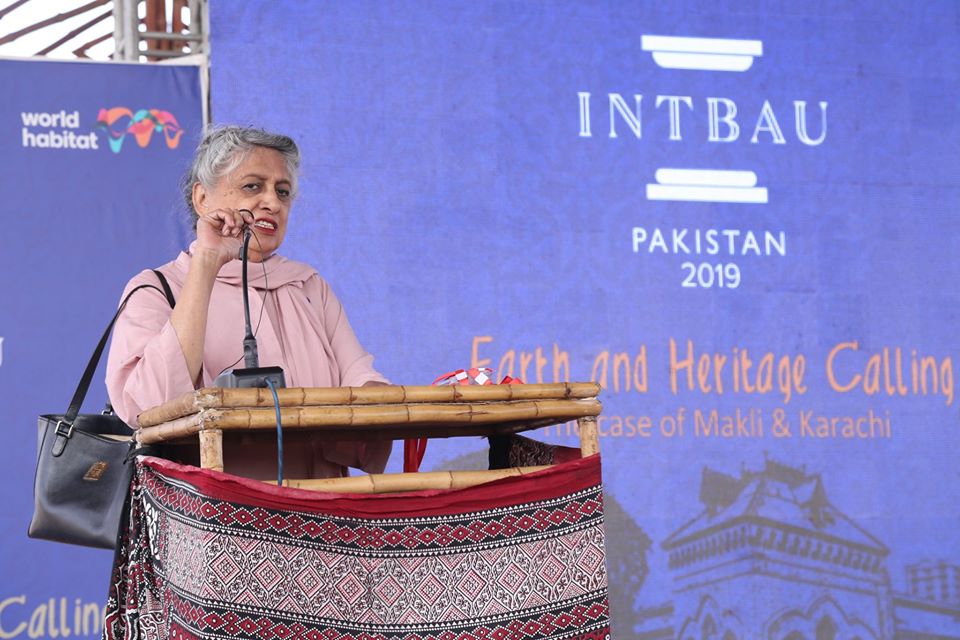

Yasmeen Lari, CEO of the Heritage Foundation, speaks at a sustainable architecture conference in Makli. Photo: Heritage Foundation of Pakistan

And therefore, the Heritage Foundation has been helping to create markets for the villagers in the area. For instance, in Mirpurkhas, located a few hours away from Makli, the foundation is helping villagersto build toilets in their homes and the terracotta basins for the toilets are sourced from one of the Makli villages specialising in Kashi.

It’s a case of “the poor helping other poor”, says Lari.

A special emphasis is also laid on inclusivity, with 50 people with disabilities trained as part of the programme. Women and young people also attend in large numbers.

Working with a beggar community

But getting a project like this going in a place like Makli was no mean feat, for while the Heritage Foundation had past experience of working with impoverished communities, it hadn’t dealt with this level of poverty.

“The communities we work with are all beggars – they are not only living below the poverty line but are absolutely at the bottom of the poverty line,” explains Lari.

Such is the level of destitution that children suffer from stunted growth due to malnourishment and women can have as many as 15 children. A pre-project survey had revealed that some people in the area were living with zero income and some families were earning a maximum of 2,000 rupees (£10) a month – which they obtained mostly through begging.

A woman cooks on a chulah – smokeless earthern stove. Photo: Heritage Foundation of Pakistan

And so, before anything, it was a matter of earning the locals’ trust. The Heritage Foundation did so by first installing water hand pumps in the area and providing support to build bamboo shelters for the homeless. Once this relationship was developed, the villagers started becoming keener to learn various skills that could provide them a sustainable source of livelihood.

The next step was creating financial literacy; the trainers had to teach the villagers how to manage their money and why it was important to save for the future.

Lari recalls the success story of a woman named Kareema, who was the first villager who had decided to give up begging and learn the art of Kashi. She started selling handicrafts and jewellery to tourists and motorists at the same spot where she used to beg, and began to earn money.

The Heritage Foundation aims at taking a majority of the villagers above the poverty line, meaning they earn above 6,000 rupees (around £30) per month.

Ghulam Abbas (pictured top with Marbee), a local artisan who helps with the teaching, recalls that outsiders would mostly avoid any sort of contact with the beggar community, but that is now changing.

“A beggar is not seen with respect, but a skilled person is held in high regard,” he says.

A Makli villager welcomes buyers at her stall of terracotta products in Makli. Photo: Adeel Ahmed

Not the ‘western charity model’

The focus of the programme has been to develop the capacity of the villagers and help them gain a source of sustainable livelihood, instead of doling out funds among them.

“I think the international model is totally wrong,” argues Lari. “So much money has been spent in this country that has come in due to [(natural]) disasters, but where is it? It’s not sustainable because we are not teaching people but making things for them. So the western charity model is not working for us.”

And this is where the British Council’s Developing Inclusive and Creative Economies (DICE) programme is helping. Unlike projects which are focused on achieving some material outcome, the funding from DICE helped the Heritage Foundation with training the Makli villagers.

“[Through DICE] we have done training on a massive scale…and now the results are coming in,” Lari told Pioneers Post.

The funds are also used to arrange transport for participants to attend the trainings and to provide them with lunch. No cash is given out.

The foundation’s previous collaboration with University of Glasgow academics Dr Azra and Peter Meadows helped with the project development.

Terracotta jewellery make by Makli villagers. Photo Adeel Ahmed

“Dr Azra and Peter Meadows have been our long-term partners; they have done a lot of work for humanitarian causes,” says Lari of the partnership.

“Although the technique was ours, I had wanted them to come and review, and they do a kind of independent monitoring of the work. They assess the work that we do and tell us where we can improve.”

But despite all the work her organisation has been doing to help the people of Makli, Lari considers it to be “a drop in the ocean” — considering the level of poverty and need. But the goal going forward is to scale up and reach maximum numbers.

“I don’t know what it will take; I have no idea yet. But I have to take it forward,” she concludes.

Adeel Ahmed is a DICE Young Storymaker – one of 14 young journalists recruited by Pioneers Post and the British Council from six countries to report on social and creative enterprise.