‘Our biggest enemy is ourselves’ – innovation guru Ann Mei Chang tells impact funders to raise the bar on risk-taking

Mission-driven investors and philanthropists must make ‘dramatic shifts’ in how they operate – or risk a future where many who are disadvantaged are left even further behind.

Ann Mei Chang, whose innovation credentials span from roles at Apple and Google to chief innovation officer at USAID – and a recent stint as CIO for presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg – called on organisations across the impact space to “become more nimble, more bold, more collaborative, and of course more innovative” in order to “blaze new paths to shape our world for the better”.

Ann Mei Chang, whose innovation credentials span from roles at Apple and Google to chief innovation officer at USAID – and a recent stint as CIO for presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg – called on organisations across the impact space to “become more nimble, more bold, more collaborative, and of course more innovative” in order to “blaze new paths to shape our world for the better”.

She pointed to three tools that could work together to make this happen: an increase in so-called ‘tiered funding’ – where funding is arranged into multiple, escalating tranches based on performance rather than making a single, up-front investment; greater support for experimentation in the form of challenges and prizes, and an increase in ‘outcomes-based’ funding such as impact bonds or simpler ‘outcomes bonuses’.

Chang – whose book, Lean Impact, explores ‘how to innovate for radically greater social good’ – made the recommendations in her keynote speech for day two of EVPA’s annual conference.

Speaking via Zoom from her home in Delaware, US, she said that “the work all of us do to tackle long-standing and entrenched ills in our society” had “always involved huge challenges and required innovative solutions” for public and private sector failure. But existing interventions “all too often fall far short of meeting the vast needs”.

Covid-19 had suddenly expanded these needs – and to make matters worse, many of those interventions that had “filled the gaps” had now themselves been disrupted. “Yet the world has been permanently changed in ways that have yet not fully revealed themselves,” she said. “And while we are still in uncharted territory, it’s clear the old status quo was flawed – we don’t want to go back.”

It’s clear the old status quo was flawed – we don’t want to go back

The good news, she said, was that many donors and investors were already moving in the right direction – with over 700 foundations recently pledging to remove restrictions and reduce administrative burdens, for example.

But while unrestricted funding was undoubtedly a step forward, it did not go far enough to encourage the “new ideas that could turn the tide for tomorrow”.

Three key mechanisms for transformation

Chang suggested three mechanisms that could help achieve this “without compromising on the flexibility organisations need to rapidly learn and adapt”.

The first, tiered funding, was “perhaps the simplest general purpose tool for encouraging innovation”, she said. “A tiered structure can encourage organisations to stretch, based on the promise of bigger investment for those who show breakout results.”

This was essentially how venture capital had fuelled innovation in Silicon Valley: “VCs place lots of smaller, riskier bets, expecting most to fail, and double down on what works.”

Chang cited a programme called Development Innovation Ventures (DIV) at USAID, designed in collaboration with Michael Kramer, one of last year’s Nobel Prizewinners in economics.

The first organisation to receive all three tiers of DIV funding was Off Grid Electric, now known as Zola Electric, a company in Tanzania that provides clean, affordable energy to low income rural communities in Africa. Since most families were unable to afford the up-front costs of a home solar system, Off Grid came up with a new business model, using mobile money, so that families could pay for their system with just a few dollars a week. An initial $100,000 DIV grant allowed Off Grid to test out this unproven approach and show that it could work. When it showed promise, a subsequent $1m grant enabled them to start building out their distribution and production infrastructure. Finally, a $5m stage three grant helped them unlock the commercial lending they needed to scale, by de-risking the as-yet unproven payment track record of their low income customers.

Based on these tiered grants, Off Grid was able to build a sustainable business model, raise over $150m in debt and equity and help spawn one of the fastest growing industries in Africa.

Tiered funding could also encourage innovation in the public and social sector, said Chang. She pointed to US-based donor Blue Meridian Partners, which typically makes big investments in established non-profits operating at large scale to boost the economic mobility of young people and families trapped in poverty. Its newer Studio programme offered a lower tier of more flexible funding to grantees such as OneGoal, a non-profit working to close the college degree divide between affluent and low income students in the US.

While OneGoal’s classroom-by-classroom approach had been “incredibly successful” they had only been able to reach a small fraction of the 1.4 million low-income students that could stand to benefit. After the Studio funding, they stretched their activity from classrooms to working district-wise, and were now looking at online models that could dramatically increase their ability to scale.

Challenging solutions

The second mechanism – challenges and prizes – offered a way to identify specific gaps where more effective or scalable solutions were needed, and then to draw in the ingenuity required to create those solutions. These “opened the door to many unexpected ideas”, and “doubled down on those that work best”.

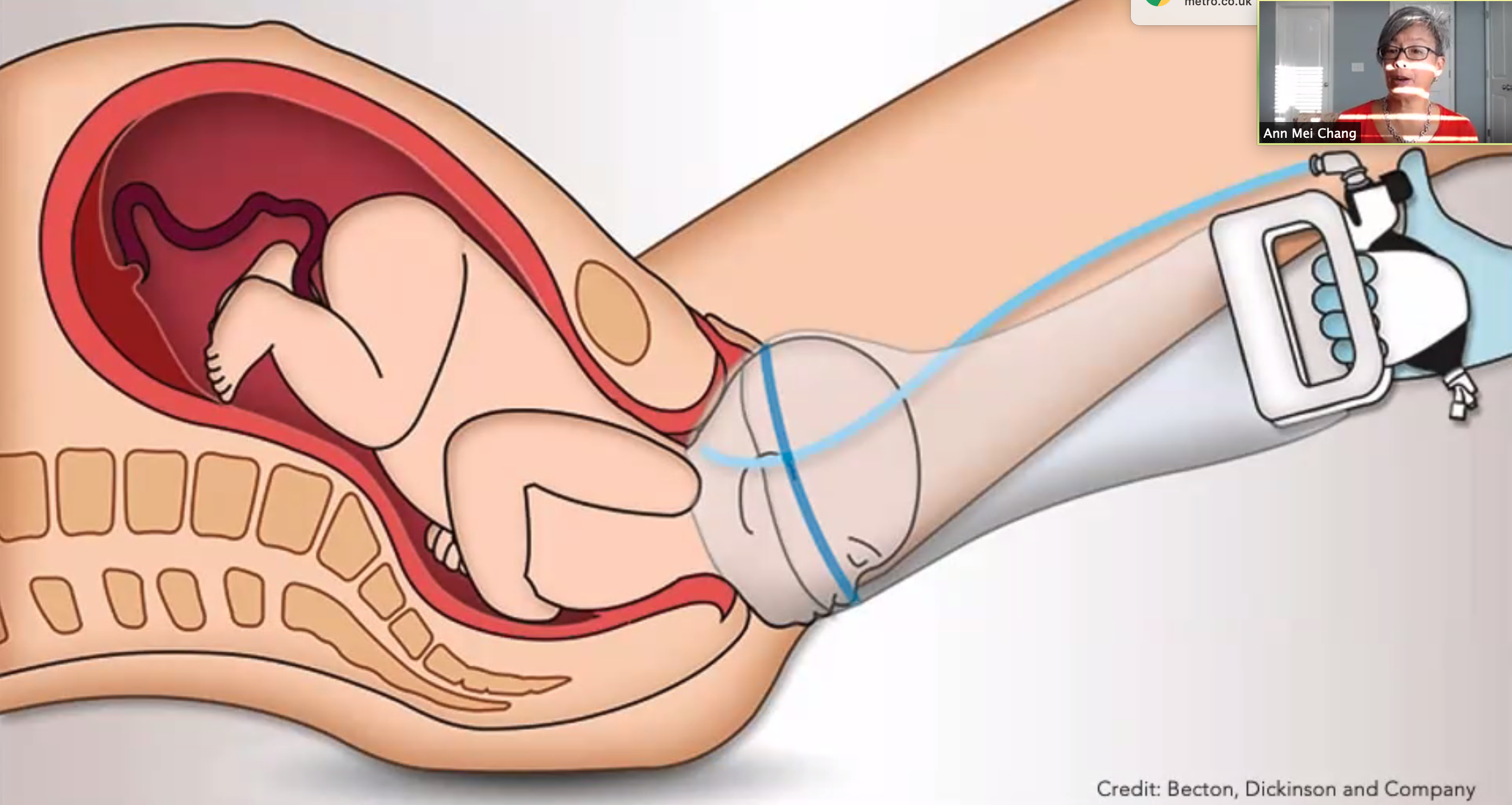

Chang again cited USAID, this time for its Saving Lives at Birth Grand Challenge, which sought better solutions for pregnant mothers and newborns during the vulnerable hours around birth. Among the winners was Jorge Odon, an Argentinian car mechanic who invented the Odon Device, a low-cost instrument to assist in obstructive birth. His inspiration had been a YouTube video for extracting a cork from a wine bottle. After early testing showed his device could be a safer alternative to forceps, particularly in low resource settings with minimally trained midwives, Jorge was able to license his design to Becton, Dickinson & Co., a large American medical technology company, who had the capacity to run clinical trials and bring it to market.

Driving performance and scale

For “more mature interventions”, said Chang, funding that focused on outcomes rather than activities or outputs was “the purest way to align on impact and incentivise improved cost-effectiveness, whilst giving organisations flexibility and again staying focused on the ends rather than the means”.

In this space, she said, Social Impact Bonds (SIBs) and Development Impact Bonds (DIBs) had drawn a lot of attention. One powerful example was Educate Girls, an Indian NGO that participated in a three-year development impact bond to identify, enrol and retain out-of-school girls in education.

“Given their payments were tied to their ability to deliver results, the bond structure pushed Educate Girls to become far more rigorous in collecting, organising and analysing impact data, to give them the visibility into their performance they needed to drive rapid improvements. As a result they were able to increase their cost effectiveness and come back from falling behind in year one and year two to exceed both their learning and their outcome targets by year three. And the systems they put in place have continued to propel them to further dramatic improvement since then.”

Simpler and more practical mechanisms such as outcomes-based bonuses could similarly encourage innovation and more cost effectiveness. For example, with the support of Third Sector Capital Partners, King County in the US state of Washington offered their outpatient mental health and substance abuse providers a 2% performance bonus based on benchmarks for a timely intake and transition to routine care.

“Even though this was only a modest bonus, it served to focus and align priorities,” said Chang. “In addition, providers were aware that an even greater portion of payments was going to be linked to outcomes in the future, and this gave them even more reason to improve – they wanted to stay competitive.”

We shouldn’t be too easily satisfied with doing some good

Concluding her presentation, Chang told conference delegates that, “as a sector, we shouldn’t allow ourselves to be too easily satisfied with the idea of doing some good”.

She continued: “I say it’s time we raised the bar. With all the challenges facing the world, on top of long-standing inequities that are only becoming more deeply entrenched, we’re going to need to stretch... Just as we have the structures, the incentives and the culture to hold companies accountable for maximising profits and maximising shareholder value, as mission-driven investors, we should hold ourselves accountable to maximising both the depth and breadth of our impact.

“To do so, we need to set our sights higher – to collaborate meaningfully across sectors, and create incentives that will encourage the risk taking and innovation needed to achieve transformational change.”

Our own worst enemy

Asked about barriers to change, Chang warned that organisations faced with addressing immediate needs could become too focused on both short-term results and with their own status quo: “We tend to fall in love with our solutions instead of staying in love with the problem.”

The biggest threat, she said, was a lack of ambition. “Our biggest enemy is ourselves – we tend to be too conservative. The risk is that we will go backwards, that we will end up even worse because the crisis has really magnified the inequities that exist in our society. But a lot of things have opened up to be open to change – if we step into that change and are willing to go forward and be leaders, we have an opportunity to truly transform our society.”

Thanks for reading our stories. As an entrepreneur or investor yourself, you'll know that producing quality work doesn't come free. We rely on our subscribers to sustain our journalism – so if you think it's worth having an independent, specialist media platform that covers social enterprise stories, please consider subscribing. You'll also be buying social: Pioneers Post is a social enterprise itself, reinvesting all our profits into helping you do good business, better.