A family affair: What stops banks and foundations who share DNA from collaborating for impact?

Ask any cousins, a mother and son or even twins if they have identical values, fall in love with the same people or make exactly the same decisions, and the answer is likely to be no. They may share much of the same DNA – but how closely they might agree (let alone work together) is hard to predict.

And so it appears to be for banks and their associated foundations.

At a session exploring ‘fruitful collaborations’ between banks and foundations at the EVPA conference this week, it was striking how differently such relationships could work. Both in terms of the relationships themselves – how they had come about, how close, which side had the power – and also in their ability to work together to achieve joint aims.

Three different models were presented at the conference session: a 15-year-old foundation that owns its 200-year-old bank; an established trust that founded a bank (which in turn founded its own private equity arm), and a – perhaps more typical – five-year-old foundation set up to co-ordinate its parent bank’s philanthropy.

Shareholder power

Franz-Karl Prüller, senior advisor to the board of Erste Foundation in Austria, explained that Erste Group Bank, founded in 1819 as the first Austrian savings bank, was itself set up as a social enterprise specifically to support people “at the margins of society” with no previous access to banking. The bank is now a stock exchange listed company with 16 million clients and Euros 265 billion of assets.

Franz-Karl Prüller, senior advisor to the board of Erste Foundation in Austria, explained that Erste Group Bank, founded in 1819 as the first Austrian savings bank, was itself set up as a social enterprise specifically to support people “at the margins of society” with no previous access to banking. The bank is now a stock exchange listed company with 16 million clients and Euros 265 billion of assets.

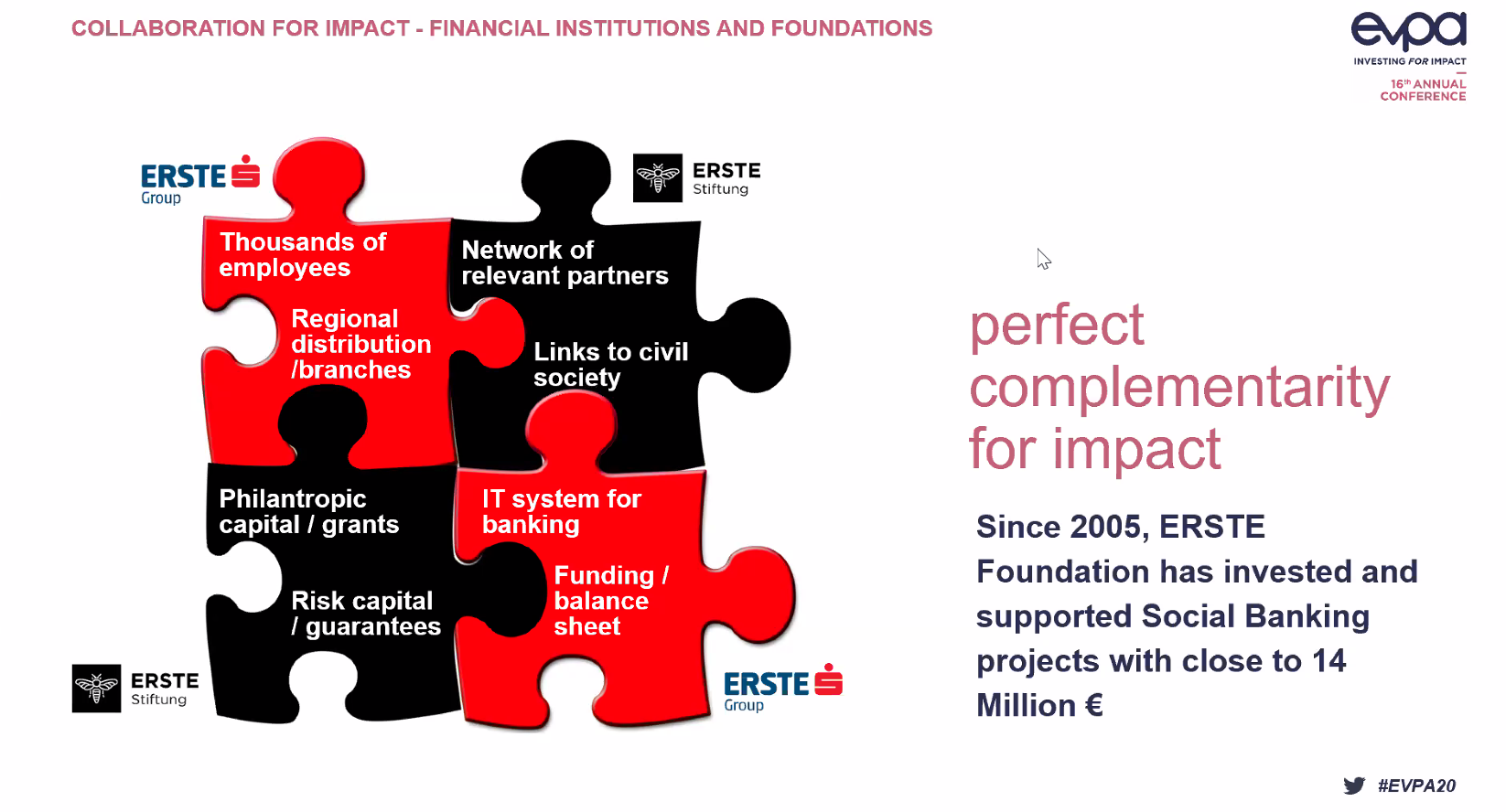

With close to 40,000 employees, more than 16 million customers and almost 3,000 branches in central and western Europe, the bank had “huge leverage” that could “be brought to bear on societal developments and concrete actions in the societies where the bank is active”.

Since the foundation launched in 2005 it had “been trying to work closely with the bank in creating new ideas of how the old, basic mission” could be translated to meet today’s needs.

The foundation is also the bank’s largest shareholder (with 11% of the shares). “As a shareholder we have a very direct link to the bank,” said Prüller. “We together, bank and foundation, have been able together to develop a number of very interesting measures we have introduced in the last 15 years.”

One of these involved the launch of a second savings bank which has served more than 12,000 customers in Austria – people who would have had access to banking any longer because of their financial problems – into which the foundation invested close to Euros 14 million.

One of these involved the launch of a second savings bank which has served more than 12,000 customers in Austria – people who would have had access to banking any longer because of their financial problems – into which the foundation invested close to Euros 14 million.

The foundation has also been building a network of civil society partners, experts in social integration and social enterprise building, and raised awareness not only in civil society but with politicians and people in industry and commerce – laying the groundwork for concrete products and services that the bank could offer.

While the bank provided loans and advice, the foundation could offer complementary philanthropic grants and risk capital/guarantees to serve customers otherwise beyond the reach of the bank.

The combination of grants and guarantees with the bank’s loans are a key element of how the organisations come together to provide services they wouldn’t normally be able to offer alone.

Asked if there were challenging situations where the bank and foundation wanted to push in different directions, Prüller could name two: first, when the foundation first launched, the bank fell into the trap of seeing it as “the CSR department”.

Prüller explained: “We very clearly said, no guys, this is not what we are supposed to be. We are a responsible shareholder, therefore we act in civil society as we are acting, but it does not mean that the bank itself can just focus on the brutal profit maximising… the bank needs to think itself about how it lives social responsibility.”

We very clearly said, no guys, this is not what we are supposed to be... it does not mean that the bank can just focus on the brutal profit maximising

The second challenge was a push back from the bank about creating the separate savings bank for people with financial problems – or “people that no other bank wanted to have any more”.

“We had really to fight with the board...[who] saw this as only a loss making proposition. We had to really push hard to overcome a certain reluctance to deal with people at the very bottom of society.”

Peter Surek, head of social banking at Erste Group Bank AG, said promoting social finance inside a regular, stock-listed bank and reaching scale was “really a challenge”, if you “don’t want to do it only as a CSR programme but also plug it into the business lines as we did”.

Peter Surek, head of social banking at Erste Group Bank AG, said promoting social finance inside a regular, stock-listed bank and reaching scale was “really a challenge”, if you “don’t want to do it only as a CSR programme but also plug it into the business lines as we did”.

A flowing ecosystem

The second model explained was the GLS Trust, described by head of impact investment Dr Martina Mettgenberg-Lemière.

GLS Trust was founded in 1961, and is an association of more than 370 charity organisations. In 1974, the GLS Bank was launched and in 1995 the bank founded a private equity arm. The bank was originally founded with a focus on ecological, social and cultural projects, particularly anthroposophic schools, but it has broadened out to include renewable energy and the social economy.

Mettgenberg-Lemière said the GLS Group perceived its different organisations as operating in a kind of natural ecosystem through which money was constantly flowing and being pooled, distributed and recycled.

Mettgenberg-Lemière said the GLS Group perceived its different organisations as operating in a kind of natural ecosystem through which money was constantly flowing and being pooled, distributed and recycled.

In total, the GLS Trust holds Euros 135 million assets under management, including Euros 60 million mainly invested directly into social enterprises (in a variety of forms, including equity, debt, convertibles and options) as well as Euros 30 million of publicly listed stock, on which the bank advises.

Sometimes they play us and the bank against each other so we have to be careful of that

As with the Erste example, the foundation will often take on a risk – in the form of a subordinated loan – while the bank may take the secure part of it. “So together we will get this organisation through their entire financing. We may take the first risk and after that the bank comes in. Sometimes we pool money with three or four other actors,” said Mettgenberg-Lemière.

However, despite the close collaboration with the bank, there can also sometimes be competition. Since both organisations are involved in direct investment into social enterprises, they can find themselves speaking to the same potential investee without each other knowing they were both involved.

“Sometimes they play us and the bank against each other so we have to be careful of that as well,” said Mettgenberg-Lemière.

Perfect independence

In the third model, Claudia Belli, head of socal enterprises and microfinance at the French bank BNP Paribas, described the relationship between the bank and the BNP Paribas Foundation as “perfectly separate”.

The foundation “works independently from the Group CSR, save from the global strategy”, she said.

The foundation “works independently from the Group CSR, save from the global strategy”, she said.

Some 68% of the BNP Group's annual Euros 45 million corporate philanthropy budget focuses on very specific programme areas such as benefiting poor neighbourhoods, supporting research on climate change or emergency relief through the Rescue & Recovery Fund that matches the amount of donations from the Group's staff and customers in France.

The philanthropic spend of the foundation has powerful impact but is strictly controlled. Although the bank and the foundation have shared values and follow the same group strategy, this does not automatically translate into working together.

In climate change, for example, the foundation might fund important new research, which is not fundable otherwise, while the bank would run a separate project to fund the enterprises on the search for climate change solutions.

Belli cited another example involving the bank’s work in structuring 10 social impact bonds (SIBs) – seven in France, one in Belgium and two in the US. For the US SIB and one of the French bonds, BNP Paribas had been working with different foundations who were either outcome funders or guarantors – but would not work with its own foundation “simply because it’s not in scope”.

“The day we would have something perfectly fitting then maybe they would work with us, but they are completely independent,” Belli explained.

Thanks for reading our stories. As an entrepreneur or investor yourself, you'll know that producing quality work doesn't come free. We rely on our subscribers to sustain our journalism – so if you think it's worth having an independent, specialist media platform that covers social enterprise stories, please consider subscribing. You'll also be buying social: Pioneers Post is a social enterprise itself, reinvesting all our profits into helping you do good business, better.