Who is the investor and what do they want to know?

Are we all in denial or do we actually care about organisations' ability to generate financial returns at the same time as value for others? We need to close the gap between what businesses are expected to report on and what they would be held legally accountable for, argues Jeremy Nicholls – if, that is, we are going to have businesses acting in ways that we, the actual asset owners, would expect.

Stock markets are up? Good news for all. Stock markets are down? Gloom and doom.

For most of us, even if we have some of our pensions invested in a stock market, whether the markets are up 1% or down 1.5%, doesn’t mean much to our daily lives. In the event of a ‘crash’, as in 2008, then, yes, we all see and feel the consequences but most of the time the daily stream of market information isn’t that relevant. And yet, of course, listen to the news and the importance of responding to ‘the market’, making sure we meet investors’ needs and expectations is critical.

In late 2020, the IFRS, the body responsible for setting international accounting standards, launched a consultation on whether a Sustainability Standards Board should be set up alongside the existing Accounting Standards Board. One of the key questions was whether the focus should be on information that was financially material. This is information that matters as it affects a business’ expected financial returns, and it is information for investors because they are interested in the financial returns.

They are not alone. Many of the organisations that support better reporting and management of sustainability issues focus on investors, for example:

The International Integrated Reporting Council:

Providing investors with the information they need to make more effective capital allocation decisions will facilitate better long-term investment returns.

The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board:

SASB connects business and investors on the financial impacts of sustainability.

The Finance Reporting Council:

We regulate auditors, accountants and actuaries, and we set the UK’s Corporate Governance and Stewardship Codes. We promote transparency and integrity in business. Our work is aimed at investors and others who rely on company reports, audit and high-quality risk management.

The Principles for Responsible Investment:

The PRI is truly independent. It encourages investors to use responsible investment to enhance returns and better manage risks, but does not operate for its own profit; it engages with global policymakers but is not associated with any government; it is supported by, but not part of, the United Nations.

The above references, taken from their website, should perhaps come as no surprise, since it is investors that invest in businesses and businesses which either detract from or contribute to sustainability.

But this all begs the question – who are these investors and what do they want to know? They are interested in financial returns and so they are interested in information that helps them assess those returns, and this includes the consequences or impacts the organisation has on others, to the extent these impacts affect the financial returns.

Getting to carbon zero cannot be a good thing regardless of what happens to our already ridiculous wealth distribution

Sustainability ‘issues’ are increasingly recognised as increasing the riskiness of those returns. As the IIRC International <IR> Framework states: Providers of financial capital are interested in the value an organisation creates for itself. They are also interested in the value an organisation creates for others when it affects the ability of an organisation to create value for itself.

And so to the world of Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) reporting, non-financial reporting, integrated reporting, sustainability reporting, etc, etc. All of which can be sources of this information.

Of course, some ‘issues’ are more important to investors than others. Climate change is the biggy. Wealth inequality….? Not so much. But getting to carbon zero cannot be a good thing regardless of what happens to our already ridiculous wealth distribution. In terms of the SDGs if 50% of carbon is generated by the richest 10%, perhaps SDG 10 on inequality is more important than SDG 13 on climate action?

A question of ownership

It all comes back to the question of who are the investors and what do they want?

Much of the money invested in companies is through stock exchanges. Most is invested by investment managers on behalf of others. So there is a recognised differentiation between asset managers and asset owners. Unfortunately, asset owners are treated as including pension funds even though they are trustees, acting in the interests of the actual asset owners.

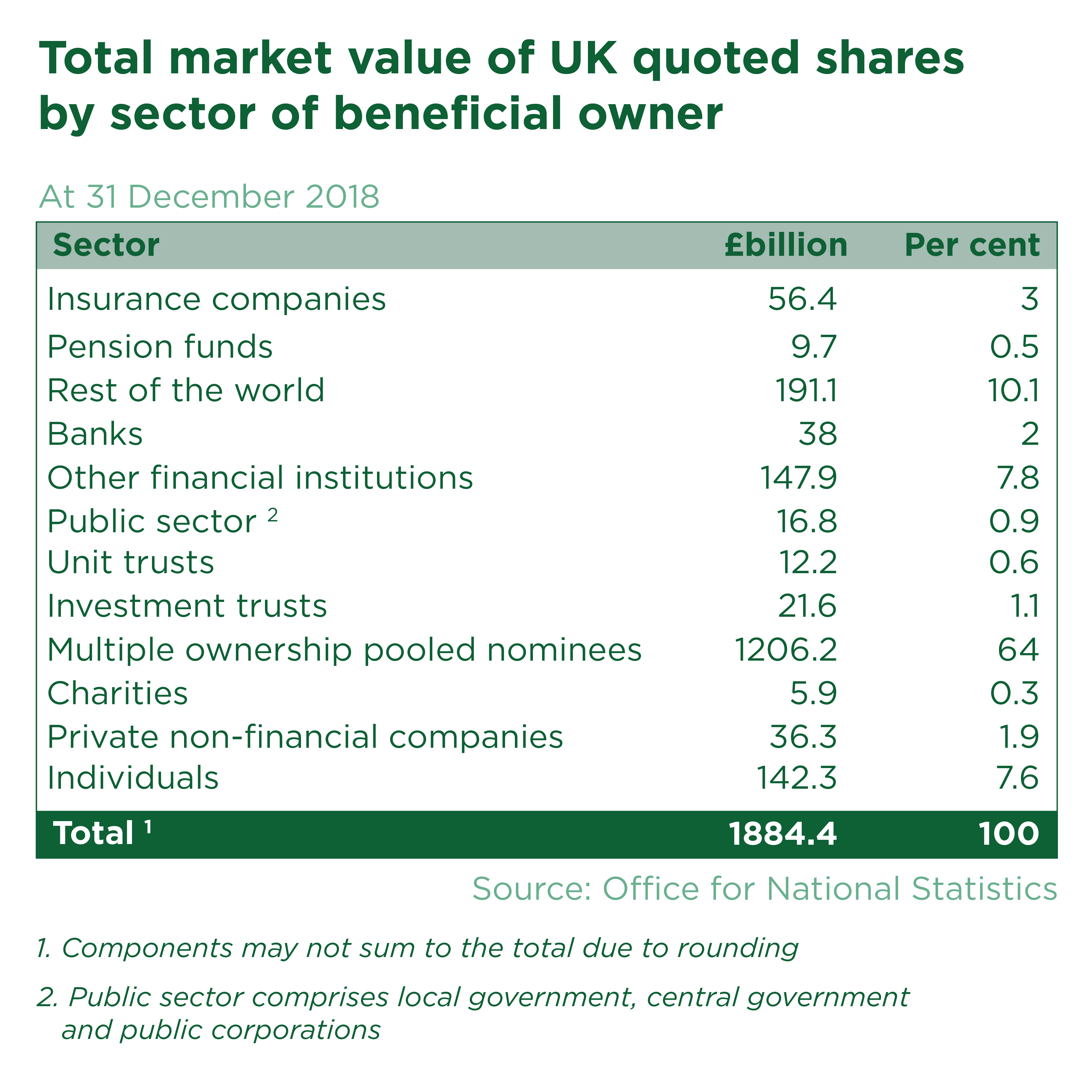

The investors are the people who own those pensions – you and me if we are lucky enough to have one. The Table below shows a breakdown of share ownership. Individuals own less than 10%, although the share of individuals in ‘rest of world’ is not reported. And the pooled nominee holdings, over 60%, are held in trust by your broker.

It makes sense that all these organisations would be interested in those risk adjusted financial returns – because that’s what the actual asset owners want isn’t it?

Or not.

Little is known about the motivations and interests of the actual asset owners, and even less about how that varies by gender, race or class. Certainly ownership is not evenly distributed. In the US, 84% of all stocks owned by Americans belong to the wealthiest 10% of households.

Little is known about the motivations actual asset owners, even less about how that varies by gender, race or class.

If we were told that being interested in financial returns means being interested in financial returns irrespective of anything else that happens that doesn’t affect those returns, we might stop and think. And then carry on, assuming a business surely cannot go around making money at any cost without breaking the law.

This world looks something like this. All is well. Businesses provide the things we need, and the law stops any dodgy practices.

Of course, on reflection we realise it’s a bit more like the next diagram. Not all the dodgy practices get picked up and not all companies and their directors get held to account. But the world is not perfect and the benefits exceed the costs so…

In reality there is a whole world where business does have effects on other people, where these effects are not illegal, where managers may agree that they are not entirely responsible but are nonetheless a ‘cost of doing business’. These are consequences of a business’ operations that do not have, or at least are not assessed as having, an effect on its ability to generate financial returns. Making money at any cost so long as it is someone else’s cost, which looks a bit more like this.

And, of course, isn’t the whole point of having a business to internalise income and externalise costs? Which is to reinforce, as I argued in my last article in this series, an approach that can be described as being in denial of the consequences of our actions. We need to close the gap between what businesses are expected to report on and what businesses would be held legally accountable for. If, that is, we are going to have businesses acting in ways that we, the actual asset owners, would expect, ways which contribute to sustainability or even better, to a regenerative economy.

Closing the gap

There are a few ways to close the gap. A more holistic approach to accounting and a more effective legislative environment would help. A more holistic approach would include anything that affects investors' decisions, the more that the consequences of a business’ operations affect the value of the business and its ability to generate returns, the more those consequences will influence investor’s decisions.

Currently the basis of financial accounting, taken from the IFRS Conceptual Framework’s introductory paragraphs, basically sets out the same position as where we started. Investors are interested in financial returns and need to assess the ability of a business to generate net cash inflows:

The objective of general purpose financial reporting1 is to provide financial information about the reporting entity that is useful to existing and potential investors, lenders and other creditors in making decisions relating to providing resources to the entity.2 Those decisions involve decisions about:

(a) buying, selling or holding equity and debt instruments;

(b) providing or settling loans and other forms of credit; or

(c) exercising rights to vote on, or otherwise influence, management’s actions that affect the use of the entity’s economic resources.

The decisions described depend on the returns that existing and potential investors, lenders and other creditors expect, for example, dividends, principal and interest payments or market price increases. Investors’, lenders’ and other creditors’ expectations about returns depend on their assessment of the amount, timing and uncertainty of (the prospects for) future net cash inflows to the entity and on their assessment of management’s stewardship of the entity’s economic resources. Existing and potential investors, lenders and other creditors need information to help them make those assessments.

To make the assessments, existing and potential investors, lenders and other creditors need information about:

(a) the economic resources of the entity, claims against the entity and changes in those resources and claims (see paragraphs; and

(b) how efficiently and effectively the entity’s management and governing board3 have discharged their responsibilities to use the entity’s economic resources.

Is this all they are interested in?

The Conceptual Framework recognises that:

Individual primary users have different, and possibly conflicting, information needs and desires. The Board, in developing Standards, will seek to provide the information set that will meet the needs of the maximum number of primary users. However, focusing on common information needs does not prevent the reporting entity from including additional information that is most useful to a particular subset of primary users.

…And is therefore arguing that interest in financial returns meets the needs of the maximum number of primary users. Research by SVUK with YouGov suggested this was not the case. Asked about what information they would want from the accounts only 15% were only interested in their expected financial returns. To one extent or another everyone else wanted to know something about the impacts on others, the returns to other stakeholders, the consequences of the business operations.

This is not to argue that, by itself, this research proves that the maximum number of users have different information needs but to argue that now is the time to reassess the common information needs of the maximum number of users. Even so, the results shouldn’t be that surprising. Even Adam Smith, in The Theory of Moral Sentiments, realised it:

“How selfish man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it.”

A matter of potential

Perhaps most importantly though, in case you missed it, the IFRS clearly states existing AND POTENTIAL investors. Not only people currently investing but also those that might. Not only the 10% that own 84% of stocks but the percentage that own none. People who have or show the capacity to develop into investors in the future.

Surely that is all of us? Unless we are saying that the poor have no capacity to become rich enough to invest whilst including an investor buying a future contract that could lead to their bankruptcy. And don’t forget that the public sector, acting in all our interests by law, is an existing investor. It is not just what today’s actual investors want, it also what potential investors want, which includes all those people currently experiencing the consequences of a business’ operations. This is fundamental in deciding what investors want. Some may be concerned that this approach leaves the focus on investors as opposed to a multi-stakeholder approach. But if all these stakeholders are included because they are potential investors, then want they want should be considered. Easier perhaps to win this argument than to get ‘the market’ to move away from the primacy of ‘the investor’.

There is a lot of debate at the moment on the difference between financial materiality and stakeholder materiality, what the IFRS consultation referred to as double materiality. If potential investors means all of us, then there is only one type of materiality, what matters to current and potential investors.

The real issue is that this is more than just the financial returns, even if those financial returns are taking sustainability risks into account, a perception that is rooted in history and now in fiduciary law and in accounting practice. People, those actual and potential asset owners, may not be only interested in the financial returns. They may be interested in an organisation's ability to generate financial returns and value for others, irrespective of whether that wider value has implications for their returns. If so, we need to update both law and practice. Changing accounting is as easy as changing the introductory paragraphs of the Conceptual Framework. In my first article I argued we need to take a gender, race and class lens to consider what investors common information needs might be but, for example, it might end up saying that investors need information to assess their expected returns and the expected impacts on others, rewording the Conceptual Framework…

The objective of general purpose financial reporting is to provide financial information about the reporting entity that is useful to existing and potential investors, lenders and other creditors in making decisions relating to providing resources to the entity. Those decisions involve decisions about:

(a) buying, selling or holding equity and debt instruments;

(b) providing or settling loans and other forms of credit; or

(c) exercising rights to vote on, or otherwise influence, management’s actions that affect the use of the entity’s economic resources.

The decisions described depend on the returns that existing and potential investors, lenders and other creditors expect, for example, dividends, principal and interest payments or market price increases and the impacts of the business on others. Investors’, lenders’ and other creditors’ expectations about returns depend on their assessment of the amount, timing and uncertainty of (the prospects for) future net cash inflows to the entity, future impacts of the entity on all capitals, and on their assessment of management’s stewardship of the entity’s economic resources. Existing and potential investors, lenders and other creditors need information to help them make those assessments.

To make the assessments, existing and potential investors, lenders and other creditors need information about:

(a) the impact of the entity of all capitals, the economic resources of the entity, claims against the entity and changes in those resources and claims (see paragraphs; and

(b) how efficiently and effectively the entity’s management and governing board3 have discharged their responsibilities to use the entity’s economic resources.

There is also a wider point. Unless you are Scrooge the point of these returns is to exchange money for other things that increase your quality of life, well-being or life satisfaction. In other words, as recognised by all the organisations I quoted above, the point of all these investment returns is for a wider social purpose than the financial returns.

IFRS:

The IFRS Foundation is a privately organised, not-for-profit organisation established to serve the public interest.

SASB:

Our Vision: global capital markets in which a shared understanding of sustainability performance enables companies and investors to make informed decisions that drive long-term value creation and better outcomes for businesses and their shareholders, the global economy, and society at large.

FRC:

Successful businesses are important to the UK. They provide jobs, help the economy to grow and the nation to prosper. Our role supports this and the public wellbeing by promoting improvement in the quality of the work of auditors, accountants and actuaries so it is trusted by investors who support companies over the long term.

All these organisations realise the point of their work is for society as a whole, for public well-being, for the public interest. Literally in the interest of the public. Interests which are clearly not limited to financial returns. Given accounting need to represent the common interests, there is a role for governments to decide what those might be, for inclusive growth and a sustainable society.

Perfect sense

That’s it. The accounting and auditing profession would have to get on with working out how to do this, making sure that the information remained relevant and to use accounting language, capable of faithful representation. There is now though a considerable body of practices across communities such as the Capitals Coalition and Social Value International on what this might look like. The sheer scale of practice that would follow these changes would quickly result in standards, which of course would continue to develop over time. It might not be perfect, but it would quickly be better than the current state of affairs. It would force us to account for the consequences of business operations on others, on people and planet. And next time someone says the investor wants this or that, its worth checking whether they are referring to the asset manager, a trustee or the underlying actual asset owner.

Changing accounting isn’t a panacea. It is one piece of an accountability framework that would drive investments that create financial returns for investors with sustainable, or even regenerative, value for others.

- The next article will look more closely at how accounting can help make sure this new information is useful in the context of the growing demand for ESG information. The changes to the legal environment that would close the gap and make enforcement more likely come later in this series. Jeremy Nicholls is a director and one of the founders of Social Value International, and an ambassador to the Capitals Coalition

Thanks for reading Pioneers Post. As an entrepreneur or investor yourself, you'll know that producing quality work doesn't come free. We rely on our subscribers to sustain our journalism – so if you think it's worth having an independent, specialist media platform that covers social enterprise stories, please consider subscribing. You'll also be buying social: Pioneers Post is a social enterprise itself, reinvesting all our profits into helping you do good business, better.