Six social enterprise essentials: Why true social enterprises reject hierarchy and embrace democracy

Social enterprise has drifted too far from its roots, says Freer Spreckley, who was among the first to formulate the concept in the UK in the 1970s. In this second exclusive adapted from his new book, the social enterprise pioneer sets out six key principles that should define social enterprise. This time: why democratic governance – from wage parity to rotating roles – makes for a more efficient organisation and happier, more confident workers.

Organisations have to be efficient, and work has got to be enjoyable. Fortunately, these two things can co-exist. The secret is in the structure.

Many things influence the way social enterprises are structured, such as the ownership system, mission, commercial sector, level of technology, size, people involved, etc. But in all cases, the structure should enable things to get done with minimum effort and no waste, through good working practices that are a joy to participate in.

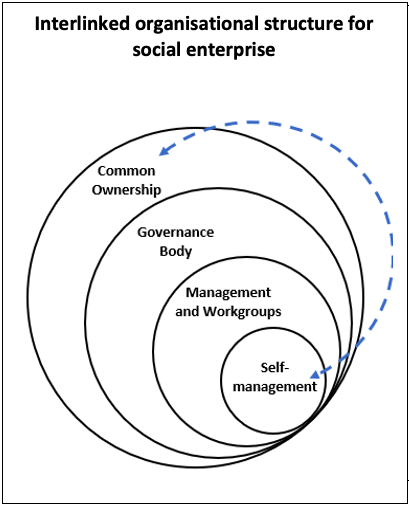

The structure of a social enterprise has four broad functions, with control resting in the common ownership structure. Ownership determines who controls the organisation, how decisions are made, and who is involved. The governance body decides policies, aims and objectives, organisational rules, strategy, planning, investment, organisational systems and accountability. Management and workgroups are responsible for coordinating and implementing the governance plans, day-to-day decision-making, and daily financial and administrative operations. Individual co-owners are self-managing members of teams accountable for carrying out the active tasks in the interest of the enterprise. The teams produce and deliver goods and services. Co-owners carry out the work and are part of every tier in the organisation.

The precise organisational structural functions will vary considerably from one enterprise to another, depending on operational details and the values adopted by the co-owners. In addition to the legal constitution are the internal rules. These set out the policies, terms and conditions of employment and operational policies. These are under the control of the governance body and determine the rules governing the behaviour of co-owners and how they relate to the public.

One of the most fantastic things about commonly owned social enterprise is the opportunity to arrange how it is organised

Social enterprise practises circular organisational systems and structures (as pictured above), but not always absolutely, and not always perfectly. Moving from a hierarchical approach to a circular design takes time and learning. The six values which I argue should be the foundation of social enterprise provide the basis for an excellent circular organisation: common ownership = equality; democracy = the right to participate in decision-making; financial viability = the guarantee of independence; social wealth creation = care for colleagues; environmental responsibility = care for the environment; and, social accounting and audit = being open and honest. These values should influence the enterprise's organisational structure and be reflected in how the organisation behaves in its daily operations and with its internal and external stakeholders.

Who owns, controls

In my book Essential Social Enterprise, I argue that social enterprises should be owned according to the legal common ownership structure. This establishes the fundamental rights of co-owners to own a share of the enterprise. It means that everyone who creates the wealth of an enterprise and contributes to its sound management and responsible behaviour is the beneficiary of the financial, social and environmental wealth generated.

A worker, an owner and a governor all in one – or, as I call it in the book, a co-owner. This is one of the most fantastic things about commonly owned social enterprise: the opportunity to arrange how it is organised.

Democracy or hierarchy?

The general and historical case against direct democracy is that working people will vote in favour of self-interest and, supposedly, professional and wealthy people will vote on merit. Needless to say, this rationale is nonsense and is always put forward by the professional and monied classes, whose interest is to maintain the status quo. History is stories of hierarchy, assumed or unchallenged. It is how things are organised, from shopping lists to the monarchy.

Hierarchy is unconscious, oppressive and personally demeaning. Democracy is conscious, uplifting, full of opportunities

Hierarchy is unconscious; often it is just the way it’s done, oppressive and personally demeaning. Democracy is conscious, uplifting, full of opportunities and personally esteeming. Because workplace democracy is deliberate and structured, it needs to be created and learned. And to work, it must be anchored to legally binding rules, like a registered enterprise constitution – and must practise one person, one vote decision-making.

Wage parity or differential?

Wage parity – when every worker is paid the same, no matter their level of experience or responsibilities – is a radical idea and practised by a small number of social enterprises. However, most use wage differentials, but keep the levels of wages low.

Why is wage parity worth considering? In these enterprises, many workers receive considerable in-house training so they can alternate tasks and roles, working in the same position for a few months at a time and then moving to another role. The benefit is more varied and interesting work, and workers become highly trained in several business and technical skills.

This approach works best in low-skilled sectors; whereas in high skill sectors, the task and learning rotation is longer. However, this is a decision each social enterprise has to take, usually at its inception, because once a decision to pay differential salaries or parity salaries is made, it is a difficult decision to change.

Inclusive decision-making

Democratic organisations are, I believe, more efficient than hierarchical structures. Democratic decision-making means everyone present knows as much as anyone else. Communication in meetings, working together and rotating tasks and roles is instantaneous, everyone knows what is going on, and opportunities for feedback and review abound. Also, inclusive decision-making tends to be more strategic than exclusive decision-making; open discussions mean a decision has benefited from being critiqued by different people from different positions in the organisation.

Being both a decision-maker and a follower of others' decisions instils a sense of worth for each member

Although some social enterprises practise hierarchy, with managers who exercise decision-making and coordination functions, many still tilt towards flatter team working. The balance between the team and a self-managing individual's decision-making is the combination of trust and respect. The team has to trust an individual in appropriate circumstances to make decisions that they would support if they were on hand. An individual has to respect and anticipate the team's level of support when making decisions in areas of their responsibility. The process of subsidiarity is the principle that a team should have a subsidiary function, performing only those tasks which cannot be performed at a more local level by an individual. The team, however, is responsible for creating trust and respect among its group to ensure confidence in individuals to make decisions.

Working in teams is a form of on-the-job action learning and improvement, and sharing jobs with others requires being both a leader and part of a team. Rotating tasks invigorates the practice of work, and being both a decision-maker and a follower of others' decisions broadens the understanding and instils a sense of worth for each member. The work experience gained through rotation prepares co-owners for career development, whether in their place of work or as the basis for new experiences and work opportunities elsewhere.

Leading the way: a democratic governance body

The governance body comprises co-owners. It sets policy, investment decisions, HR decisions, operational strategy and planning, and profit allocation. It is the leading authority from which all other authority emanates. In small enterprises, all co-owners are members of the governance body. In larger organisations, co-owners rotate the responsibility, thus keeping everyone involved, learning and contributing ideas, and experiencing long-term planning and short-term daily work tasks.

Democratic governance guarantees the rights of every co-owner to express their opinion on any topic. Social enterprise brings control to those who produce the wealth and localises active suffrage for local stakeholders. This will enable the entire workforce to learn how the roles are conducted through ‘lived experience’ and the knowledge necessary to perform governance tasks. And it will help build an educated and knowledgeable workforce to run the enterprises.

Beyond governance and good management, the governance body is also responsible for creating social wealth, partly in the way the body operates and partly in the policies, strategies and plans developed.

Management and workgroups: developing comptencies together

As co-owners are both workers and governors, they know what decisions have been agreed upon and why. They now need to implement the agreements and produce and deliver the goods and services at the operational level. The question we face is, do the co-owners need coordinating, or can they coordinate themselves?

There are several indicators to answer that question. Firstly, there is the commercial indicator, about productivity – will the work be done efficiently, on time and budget? Secondly, what will be the most personally rewarding – how will co-owners feel about working together, and did they feel part of the process, or was it too demanding or demeaning? The third indicator affects the whole organisation – is the way it was handled aligned with the principles of the organisation, and can it be repeated many times – is the method of working sustainable for co-owners and the social enterprise?

Being co-owners means arranging the work with a manager, rotating managers or without management. These are all possible, and experimenting with them can be measured with a set of agreed indicators. From my personal experience of living in communes and working in social enterprises, I’ve always been surprised by those who volunteer to take on a particular task or role when someone leaves. Competency is as much to do with attitude and confidence as it is with mental or physical dexterity. And attitude and confidence are partly created by the group, the team of individuals listening to and voicing opinions.

Competency is as much to do with attitude and confidence as it is with mental or physical dexterity. And attitude and confidence are partly created by the group

The thing about hierarchy is that it is everywhere, and we therefore assume it is essential. It is not.

What is necessary is to avoid the dead weight of hierarchy. The unchanging nature of pyramids of command weigh heavily on people and can, and sometimes do, squash the life out of them. There may be a place for hierarchy, but an automatic response of always arranging a group of workers into this structure creates its own problems. Hierarchies undervalue and make people feel irrelevant, thus lowering productivity and causing personal malaise. Also, democracy protects workers from intimidation and bullying, better than hierarchical organisations, I would say, because the former is open and more people are involved while the latter, bathed in secrecy, has very few people involved.

Being the boss can be a source of immense pride, or stress; being part of a group of bosses lessens both the satisfaction and the stress but increases social wealth and wellbeing. I’ve heard it said that equality is the ‘suppression of difference’. From my viewpoint, equality is the liberation from the strictures of hierarchy and the opportunity for creative expression. The adopted style of equality in social enterprise is not the suppression of the individual but the creative opportunity to excel.

Self-management, teamwork

Self-management will create what Wilhelm Reich called 'work democracy' (The Mass Psychology of Fascism, 1933) that governs the organic process of human behaviour through the natural and practical functions of life – love, work and knowledge. Reich claimed that work democracy is beyond philosophy or politics; it is logical, functional, and at the heart of natural humanness. Work is also circular, with deep action learning reflection and renewal functions. In general, social enterprise practises subsidiarity, where decisions are taken by those nearest to the point of resolution, except where the decisions may negatively affect the organisation's other considerations or its principles.

- Explore the Pioneers Post Business School: Social Entrepreneurs’ Survival Skill no. 4: Self-management

In social enterprise, the intention is to move towards self-management. Here, I refer to self-management as 'acting on your own or with others on behalf of the interests of the social enterprise'. Co-owners, who are also workers, combine a range of responsibilities and functions, enabling them to translate experience and knowledge into a new category of worker – the self-managed person. Being part of a workgroup, a self-managed person can, when needed, call upon colleagues for assistance, guidance and mutual problem-solving, thus creating a self-sustaining environment in which the whole enterprise benefits. The self-esteem experienced by co-owners is one of the most critical aspects of social wealth creation.

Working for the group and yourself, and being both a leader and a team member, is hugely satisfying. We have to enjoy the creative experience of self-management; making decisions, acting on them and being accountable fulfils basic instincts of personal worth.

Organisational change will come about if people are emotionally flexible and dextrous, and democratic organisations work when those involved can see others' views alongside their own, however difficult that may be. Self-management is needed for each person to be responsible, see and act. To think about everything as ours. We own it and are responsible for its good governance, without question. However, being a co-owner is no guarantee of being responsible; it is the building block to being conscientious. Social enterprise needs to build attraction, a safe place and opportunity so co-owners pay attention to what is happening and, in their own and others' interests, self-manage together.

- Freer Spreckley is the author of 'Essential Social Enterprise: A just transition to a regenerative fair future', published 2021, and available worldwide (print on demand) from online booksellers including Booksplease. Check back soon for the next installment in our exclusive series.

Thanks for reading Pioneers Post. As an entrepreneur or investor yourself, you'll know that producing quality work doesn't come free. We rely on our subscribers to sustain our journalism – so if you think it's worth having an independent, specialist media platform that covers social enterprise stories, please consider subscribing. You'll also be buying social: Pioneers Post is a social enterprise itself, reinvesting all our profits into helping you do good business, better.