Indigenous leaders offer collective stories of hope through year of crisis

Brazil is one of the world’s worst-hit countries by the coronavirus pandemic. One indigenous community, unhopeful of government aid beyond offers of unproven medical ‘cures’, has taken action early to prevent the virus entering their village – and is using the power of storytelling to reach and raise money from international audiences. Our DICE Young Storymaker in Rio de Janeiro, Yael Berman, finds out more.

“In our culture, when an elder dies, we lose a whole library,” says Yanama Kuikuro, president of the Kuikuro Indigenous Association of Upper Xingu. “When we heard that Covid-19 had reached Brazil, we were really concerned for the elderly.” So, he and other indigenous leaders from the Upper Xingu territory in Mato Grosso state – part of the Amazon region – set up a project to keep the virus at bay.

By 12 March, when Brazil’s first Covid-19 death was confirmed, the Kuikuro people had already started to take action. In Ipatse, a village of 400 inhabitants, they built an isolation house where those who travelled to cities for work or to buy supplies would quarantine when they came back. With a group of Brazilian and international scientists, public health and community development experts, known as the Amazon Hopes Collective, they also adapted an existing system to monitor coronavirus-related issues inside the village.

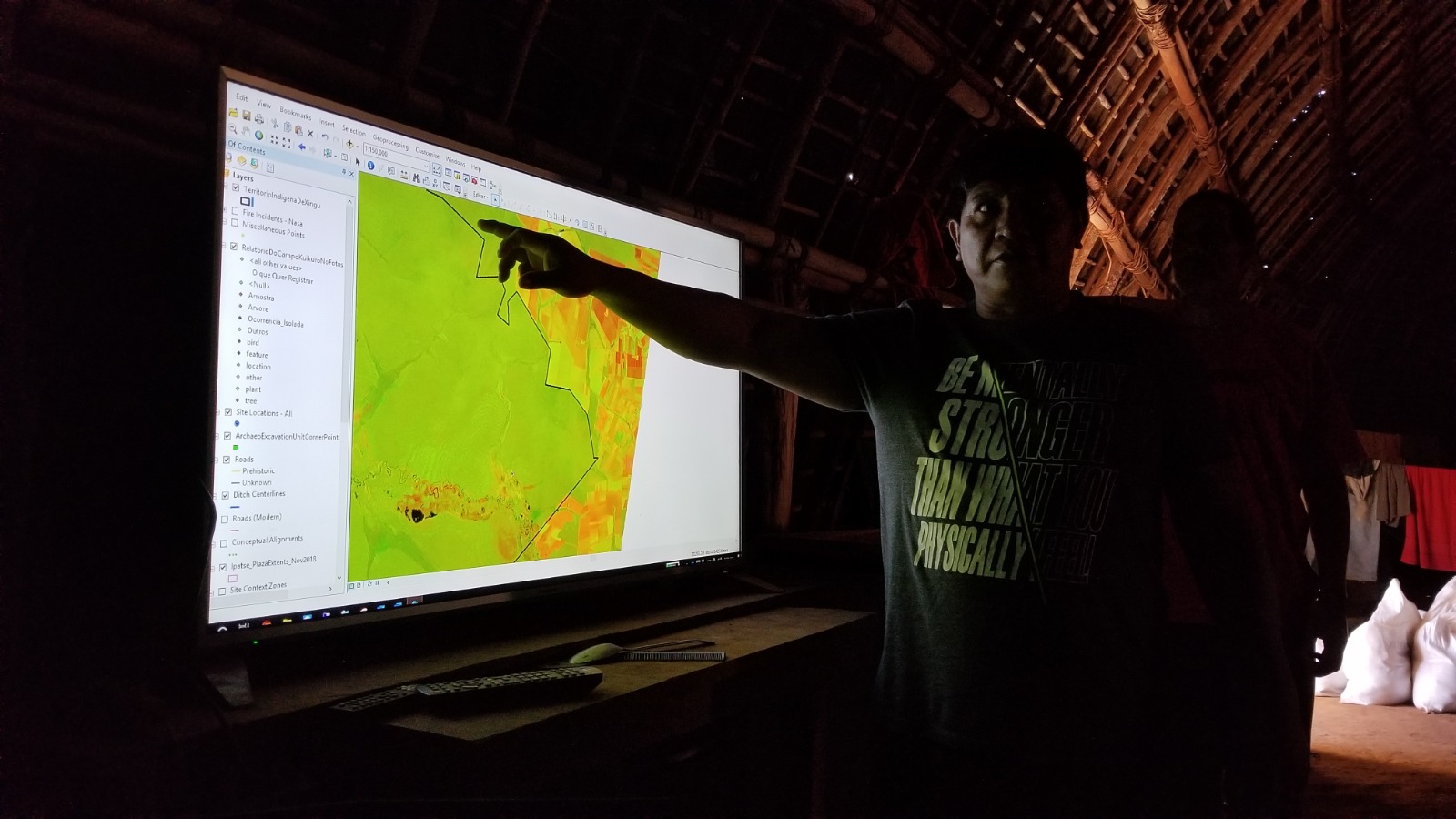

Three indigenous technicians (including Huke Kuikuro, pictured) oversee this app-based tracing system, monitoring arrivals for Covid-19 symptoms. “[They] used to monitor the territory and map trees, animals and important community cultural heritage sites,” explains Bruno Moraes, an archaeologist and member of the Amazon Hopes Collective. He explains that their aim is to address current problems in the Amazon region, such as forest fires, pollution, food security – and now, Covid-19. “When the pandemic arrived, we made improvements to the system, especially because we didn’t have a doctor in the village. Thankfully, we managed to hire one, who arrived in Ipatse village by the end of July,” says Moraes.

Three indigenous technicians (including Huke Kuikuro, pictured) oversee this app-based tracing system, monitoring arrivals for Covid-19 symptoms. “[They] used to monitor the territory and map trees, animals and important community cultural heritage sites,” explains Bruno Moraes, an archaeologist and member of the Amazon Hopes Collective. He explains that their aim is to address current problems in the Amazon region, such as forest fires, pollution, food security – and now, Covid-19. “When the pandemic arrived, we made improvements to the system, especially because we didn’t have a doctor in the village. Thankfully, we managed to hire one, who arrived in Ipatse village by the end of July,” says Moraes.

The Kuikuro Indigenous Association of Upper Xingu raised money through two fundraising campaigns, organised in partnership with the US-based Pennywise Foundation (a partner of Amazon Hopes Collective), which raised over USD $20,000, and with the UK-based People’s Palace Projects, which raised over GBP £30,000. As well as covering the construction of an isolation house and paying for the presence of a doctor in the village, these funds also paid for more than a tonne of food, 8,300 pieces of personal protective equipment (eg gloves, face shields, masks, safety glasses, aprons, thermometers, oximeters), more than five tonnes of medicine, fishing equipment and fuel.

Above: Giulia, a doctor, and Kadmiel, a nurse, pictured with a Covid-19 test. The Kuikuro Indigenous Association of Upper Xingu raised funds to pay for essential supplies, the construction of an isolation house and for the presence of a doctor in Ipatse village (credit: Kuikuro Indigenous Association of Upper Xingu, AIKAX)

Grassroots action

These provisions are helping the community to stay isolated, protecting themselves from the virus in the city. “Here [in Ipatse village] we managed to organise ourselves through the project – there was no support from the government,” says Yanama Kuikuro.

Yanama says the “lack of public policies” for indigenous communities is “damaging” during an especially tough time. Indeed, an analysis by the non-profit organisation Transparência Brasil and Abraji (the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism) showed that from April to June only 39% of the federal financial resources made available to fight Covid-19 among indigenous peoples was distributed. Meanwhile, IPAM, the Amazon Environmental Research Institute and Coiab, the Coordination of Indigenous Organisations of the Brazilian Amazon, found in June that indigenous peoples in the Amazon region were being hard hit by the virus: according to the study, the death rate per 100,000 inhabitants is 150% higher than the Brazilian average.

Above: Yanama Kuikuro showing a satellite image of the Xingu territory (credit: Kuikuro Indigenous Association of Upper Xingu, AIKAX)

Brazil's overall coronavirus death toll has passed 170,000, but President Jair Bolsonaro still minimises its severity, offering chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine – drugs with no proven effect against Covid-19 – as the ‘cure for the disease’, in his words. To date, the government has distributed almost 6 million chloroquine pills and 302,000 hydroxychloroquine pills to all Brazilian states – including indigenous communities. But some did not trust the medication. “They wanted to distribute it here [in the Ipatse village], but we didn’t accept it. Other villages did,” says Yanama Kuikuro.

The community’s efforts have prevented anyone there from contracting a serious or fatal case of Covid-19

While Ipatse village could not keep the disease at bay, the community’s mitigation efforts have prevented anyone there from contracting a serious or fatal case. Of the 881 indigenous people that have died due to Covid-19 in Brazil, according to the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB), none is from Ipatse village. Today, there are no confirmed cases there, but the villagers extended the contract of the health team in preparation for a possible second wave of the virus. And, thanks to the success of the Kuikuro Indigenous Association’s fundraising campaigns, their project was expanded to five other villages in the region. Since this happened, these villages have had no registered deaths due to Covid-19.

One of the crucial decisions taken collectively by the Kuikuro people and the other eight indigenous peoples from the Upper Xingu territory was to cancel this year’s Kuarup. Taking place between July and September, this important celebration pays homage to the dead, closing a yearlong mourning period. “I got in contact with caciques [native chiefs] from other villages through the radio and we decided to cancel it,” explains Yanama. “Holding Kuarup would have brought many people together in the village.”

Art as resistance

Others in the community have responded in their own way. The Kuikuro Film Collective made a short video announcement and posted it online in early March to alert people of the importance of staying inside the village, according to Takumã Kuikuro, one of the group’s filmmakers. (Ipatse’s inhabitants don’t have as many facilities to access the Internet as city-dwellers, but they do access the Internet regularly, through a Wi-Fi network.) He also uploaded a video showing a Kuarup celebration from a previous year. “My idea was to share it so that when people watched it, they would feel well and embraced,” he explains.

Above: Sayul Kuikuro, a member of the Kuikuro Film Collective (credit: Kuikuro Film Collective)

The films had other objectives. “We needed to show our reality, our culture, and make art from that perspective. We see filmmaking as a tool of resistance, where we can show the fight of our people. We knew we couldn’t count on the government, so we had to do it ourselves.”

We needed to show our reality, our culture, and make art from that perspective. We see filmmaking as a tool of resistance

Some of the videos were produced to raise awareness about the indigenous situation in Brazil and to raise funds. Two of these – Covid-19 Brazil - An Amazonian perspective and A view from the Xingu, both by Takumã Kuikuro – were streamed after the online version of the play The Encounter, directed and performed by Simon McBurney and co-directed by Kirsty Housley, screened in May (it was first presented in 2015, during the Edinburgh Festival). The solo performance is about a man who gets lost in the depths of the Amazon rainforest. Having first met McBurney when he travelled to the Amazon region in 2014, facilitated by People’s Palace Projects, Takumã valued this reconnection during 2020. “Being with [Simon McBurney] again, online, through this collaboration, was really important to us,” he says.

Firefighting

Though the Covid-19 pandemic isn’t over in Brazil, Takumã is focusing his productions in another direction. The end of the rainy season in the Brazilian Amazon together with deforestation and illegal mining have led to an increase in forest fires this year. From July to October 2020, there were 1,281 forest fires in the Indigenous Land of Xingu, according to the National Institute for Space Research (INPE) – an increase of 197% compared with the same period last year.

Above: The end of the rainy season in the Brazilian Amazon, together with deforestation and illegal mining, have led to a sharp increase in forest fires this year (credit: Takumã Kuikuro)

“It’s been a big problem. My father, who is 60 years old, had been infected by Covid-19 for more than 20 days,” says Takumã. “It took more time for him to recover because when he was getting better, he had got the symptoms again because of the smoke. We saw this happening to many people here. Because of the smoke, people can’t breathe, their eyes burn… This happens to everyone, and it’s even more severe for Covid-19 patients.” Forest fires also damage the plants used to make traditional medicine. “We combine the medicine from the white people with our traditional medicine. This way we managed to control the cases of Covid-19 in the village,” says Yanama.

Above: Some of the region's indigenous volunteer firefighters, who are asking for support to buy proper equipment to help them through the next months (credit: Takumã Kuikuro)

In one recent video, Takumã highlights the work of several indigenous volunteer firefighters. “We are losing natural resources, animals, many important things that connect us to nature. Climate change is more and more intense, and the world is getting warmer,” he says in the video. The firefighters and their community are asking for support in order to buy fuel, food, supplies and proper equipment to help them through the next months. Facing forest fires amid a pandemic, while feeling overlooked by the government, is no doubt a daunting prospect. Collaboration is likely to be part of the solution.

Yael Berman is a DICE Young Storymaker – one of 14 young journalists recruited by Pioneers Post and the British Council from six countries to report on social and creative enterprise.

Header image: Yanama Kuikuro filming a celebration of the Kuikuro people in Ipatse village (credit: Jair Cineasta)